Why Is Michelangelos Sistine Chapel Ceiling a Good Example of Renaissance Art? Quizlet

Michelangelo, Terminal Judgment, Sistine Chapel, fresco, 1534–41 (The holy see, Rome). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

He will come to judge the living and the dead

from the Apostle's Creed, an early statement of Christian belief

This is information technology. The moment all Christians expect with both hope and dread. This is the finish of time, the beginning of eternity when the mortal becomes immortal, when the elect join Christ in his heavenly kingdom and the damned are bandage into the unending torments of hell. What a daunting task: to visualize the endgame of earthly existence – and furthermore, to do so in the Sistine Chapel, the private chapel of the papal court, where the leaders of the Church building gathered to gloat banquet day liturgies, where the pope's trunk was laid in state before his funeral, and where—to this twenty-four hours—the College of Cardinals meets to elect the adjacent pope.

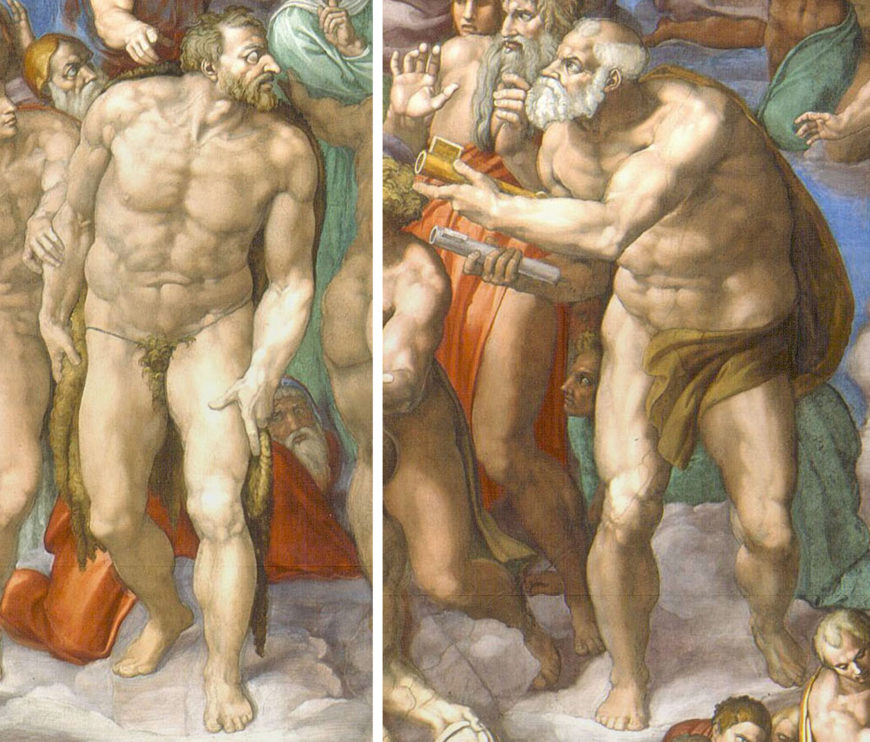

No artist in sixteenth-century Italy was improve positioned for this task than Michelangelo, whose completion of the chapel's ceiling in 1512 had sealed his reputation equally the greatest master of the homo figure—specially the male nude. Pope Paul Iii was well aware of this when he charged Michelangelo with repainting the chapel's altar wall with the Last Judgment. With its focus on the resurrection of the body, this was the perfect subject for Michelangelo.

Historical & pictorial contexts

The Last Judgment was one of the first art works Paul III deputed upon his election to the papacy in 1534. The church he inherited was in crisis; the Sack of Rome (1527) was still a recent retentivity. Paul sought to address not only the many abuses that had sparked the Protestant Reformation, but also to affirm the legitimacy of the Cosmic Church and the orthodoxy of its doctrines (including the institution of the papacy). The visual arts would play a cardinal role in his agenda, beginning with the message he directed to his inner circumvolve past commissioning the Last Judgment.

The decorative plan of the Sistine Chapel encapsulates the history of salvation. It begins with God's creation of the world and his covenant with the people of Israel (represented in the Old Attestation scenes on the ceiling and south wall), and continues with the earthly life of Christ (on the north wall). The addition of the Final Judgment completed the narrative. The papal courtroom, representatives of the earthly church, participated in this narrative; it filled the gap betwixt Christ's life and his Second Coming.

The composition

Michelangelo'southward Last Judgment is among the nigh powerful renditions of this moment in the history of Christian art. Over 300 muscular figures, in an infinite variety of dynamic poses, fill the wall to its edges. Dissimilar the scenes on the walls and the ceiling, the Last Judgment is not bound by a painted border. It is all encompassing and expands beyond the viewer's field of vision. Unlike other sacred narratives, which portray events of the past, this one implicates the viewer. It has yet to happen and when it does, the viewer will be among those whose fate is determined.

Despite the density of figures, the composition is clearly organized into tiers and quadrants, with subgroups and meaningful pairings that facilitate the fresco'south legibility. Equally a whole, it rises on the left and descends on the correct, recalling the scales used for the weighing of souls in many depictions of the Last Judgment.

Christ is the fulcrum of this complex composition. A powerful, muscular effigy, he steps forward in a twisting gesture that sets in move the terminal sorting of souls (the damned on his left, and the blessed on his right). Nestled under his raised arm is the Virgin Mary. Michelangelo changed her pose from one of open-armed pleading on humanity's behalf seen in a preparatory drawing , to one of acquiescence to Christ's judgment. The fourth dimension for intercession is over. Judgment has been passed.

Directly below Christ a group of wingless angels (left), their cheeks puffed with attempt, sound the trumpets that call the expressionless to rise, while ii others hold open the books recording the deeds of the resurrected. The angel with the book of the damned emphatically angles its downwardly to testify the damned that their fate is justly based on their misdeeds.

On the right of the composition (Christ'southward left), demons elevate the damned to hell, while angels shell downward those who struggle to escape their fate (epitome above). One soul is both pummeled by an angel and dragged by a demon, head first; a money pocketbook and two keys dangles from his breast. His is the sin of avarice. Some other soul—exemplifying the sin of pride—dares to fight back, arrogantly battling divine judgment, while a third (at the far correct) is pulled by his scrotum (his sin was lust). These sins were specifically singled out in sermons delivered to the papal court.

In the lower correct corner, Charon—the ferryman from Greek mythology who transports souls to the underworld—swings his oar every bit he drives the damned onto hell's shores (paradigm above). In the lower right corner stands another mythological grapheme, the ass-eared Minos, his ain carnal sinfulness indicated past the snake that bites his genitals. He stands at the very edge of hell, judging the new-comers to decide their eternal penalty.

Left: St. John the Baptist; right: St. Peter (detail), Michelangelo, Concluding Judgment, altar wall, Sistine Chapel, fresco, 1534–1541 (Vatican Urban center, Rome; photo: Tetraktys, public domain)

In the company of Christ

While such details were meant to provoke terror in the viewer, Michelangelo'southward painting is primarily about the triumph of Christ. The realm of heaven dominates. The elect encircle Christ; they loom large in the foreground and extend far into the depth of the painting, dissolving the boundary of the picture plane. Some hold the instruments of their martyrdom: Andrew the 10-shaped cross, Lawrence the gridiron, St. Sebastian a bundle of arrows, to proper name only a few.

Especially prominent are St. John Baptist and St. Peter who flank Christ to the left and right and share his massive proportions (above). John, the last prophet, is identifiable by the camel pelt that covers his groin and dangles behind his legs; and, Peter, the first pope, is identified by the keys he returns to Christ. His function as the keeper of the keys to the kingdom of heaven has ended. This gesture was a vivid reminder to the pope that his reign as Christ's vicar was temporary—in the end, he too volition to answer to Christ.

In the lunettes (semi-circular spaces) at the superlative right and left, angels brandish the instruments of Christ'due south Passion , thus connecting this triumphal moment to Christ'south sacrificial expiry. This portion of the wall projects one foot forward, making it visible to the priest at the altar below as he commemorates Christ's sacrifice in the liturgy of the Eucharist.

Critical response: masterpiece or scandal?

Shortly later its unveiling in 1541, the Roman amanuensis of Cardinal Gonzaga of Mantua reported: "The work is of such beauty that your excellency can imagine that there is no lack of those who condemn it. . . . [T]o my heed it is a piece of work unlike any other to be seen anywhere." Many praised the work as a masterpiece. They saw Michelangelo'due south distinct figural way, with its complex poses, extreme foreshortening, and powerful (some might say excessive) musculature, as worthy of both the subject matter and the location. The sheer physicality of these muscular nudes affirmed the Catholic doctrine of actual resurrection (that on the day of judgment, the dead would rise in their bodies, not equally incorporeal souls).

Others were scandalized—above all past the nudity—despite its theological accuracy, for the resurrected would enter heaven not clothed but nude, every bit created by God. Critics also objected to the contorted poses (some resulting in the indecorous presentation of buttocks), the breaks with pictorial tradition (the beardless Christ, the wingless angels), and the appearance of mythology (the figures of Charon and Minos) in a scene portraying sacred history. Critics saw these embellishments as distractions from the fresco'due south spiritual message. They accused Michelangelo of caring more than nearly showing off his artistic abilities than portraying sacred truth with clarity and decorum. Religious art was the "book of the illiterate" and as such should be easy to understand.

Michelangelo'due south Terminal Judgment , still, was not painted for an unlearned, lay audience. To the contrary, information technology was designed for a very specific, elite and erudite audition. This audience would empathize and appreciate his figural style and iconographic innovations. They would recognize, for case, that his inclusion of Charon and Minos was inspired by Dante's Inferno , a text Michelangelo greatly admired. They would see in the youthful face of Christ his reference to the Apollo Dais , an ancient Greek Hellenistic sculpture in the papal collection lauded for its ideal beauty. Thus, Michelangelo glosses the identity of Christ equally the "Sun of Righteousness" (Malachi 4:2).

A self-portrait

Even more poignant is Michelangelo'south insertion of himself into the fresco. His is the face on the flayed skin held by St. Bartholomew, an empty shell that hangs precariously between heaven and hell. To his learned audience, the flayed peel would bring to mind not only the circumstances of the saint's martyrdom but likewise the flaying of Marsyas past Apollo. In his foolish airs, Marsyas challenged Apollo to a musical competition, believing his skill could surpass that of the god of music himself. His penalisation for such hubris was to be flayed live. That Michelangelo should identify with Marsyas is not surprising. His contemporaries had dubbed him the "divine" Michelangelo for his ability to rival God himself in giving form to the platonic body. Oft he lamented his youthful pride, which had led him to focus on the beauty of fine art rather than the conservancy of his soul. And so, here, in a work done in his mid sixties, he acknowledges his sin and expresses his hope that Christ, unlike Apollo, will accept mercy upon him and welcome him into the company of the elect.

An epic painting

Like Dante in his neat ballsy verse form, The Divine Comedy , Michelangelo sought to create an ballsy painting, worthy of the grandeur of the moment. He used metaphor and allusion to decoration his discipline. His educated audition would please in his visual and literary references.

Originally intended for a restricted audience, reproductive engravings of the fresco apace spread it far and broad, placing it at the middle of lively debates on the merits and abuses of religious art. While some hailed it every bit the top of artistic accomplishment, others accounted it the epitome of all that could get wrong with religious art and called for its destruction. In the end, a compromise was reached. Shortly afterward the artist's expiry in 1564, Daniele Da Volterra was hired to comprehend bare buttocks and groins with bits of drapery and repaint Saint Catherine of Alexandria, originally portrayed unclothed, and St. Blaise, who hovered menacingly over her with his steel combs.

In dissimilarity to its limited audition in the sixteenth century, now the Last Judgment is see past thousands of tourists daily. However, during papal conclaves it becomes in one case once more a powerful reminder to the College of Cardinals of their place in the story of conservancy, every bit they get together to elect Christ's earthly vicar (the adjacent Pope) —the person who will be responsible for shepherding the true-blue into the community of the elect.

Additional resources:

Bernardine Barnes, Michelangelo'southward Terminal Judgment: The Renaissance Response (Berkeley: Academy of California Press, 1998).

Marcia Hall, ed., Michelangelo'southward Concluding Judgment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Loren Partridge, Michelangelo The Terminal Judgment: A Glorious Restoration (New York: Abrams, 1997).

Source: https://smarthistory.org/michelangelo-last-judgment/

0 Response to "Why Is Michelangelos Sistine Chapel Ceiling a Good Example of Renaissance Art? Quizlet"

Post a Comment